TSM&O and Infrastructure Management By Tom Kern

I would like to devote some space in this month’s newsletter to briefly discuss an area of TSMO that, historically, has not received the attention it deserves: infrastructure management. Compared to other areas of transportation infrastructure, such as pavements and bridges, TSMO-related assets frequenty do not command an appropriate level of expenditure for proper maintenance and repair, relative to magnitude of benefits that such activities can provide. This has created an opportunity for TSMO practitioners to educate legislative authorities, and the public, on the value provided by proper TSMO infrastructure management.

I would like to devote some space in this month’s newsletter to briefly discuss an area of TSMO that, historically, has not received the attention it deserves: infrastructure management. Compared to other areas of transportation infrastructure, such as pavements and bridges, TSMO-related assets frequenty do not command an appropriate level of expenditure for proper maintenance and repair, relative to magnitude of benefits that such activities can provide. This has created an opportunity for TSMO practitioners to educate legislative authorities, and the public, on the value provided by proper TSMO infrastructure management.

Consider, for example, the maintenance of traffic signals. According to the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI)’s Urban Mobility Report, approximately 295 million vehicle-hours of delay are annually attributable to these mainstays of urban and suburban intersections. Much of this delay is unavoidable, given the conflicting nature of movements that a traffic signal is meant to control. However, ITE’s National Traffic Signal Report Card estimates that current signal coordination systems have reduced this vehicle delay by nearly 10%, or just over 21 million vehicle-hours, annually. And as most agencies and the general public are keenly aware, there are always opportunities to improve signal coordination!

The potential value for reducing driver delay, harmful emissions, and fuel use through more proactive signal timing and repair factors in the tens of billions of dollars, not counting secondary benefits, such as improved safety and economic development. Yet, for an installed signal system base of just over $83 billion, public agencies across the U.S. currently have just over $1 billion to spend annually on the maintenance and repair of this infrastructure. This compares to a 2015 OECD estimate of U.S. maintenance expenditure on all public transportation infrastructure of just over $32 billion; clearly, there are opportunities to make TSMO infrastructure management a higher priority.

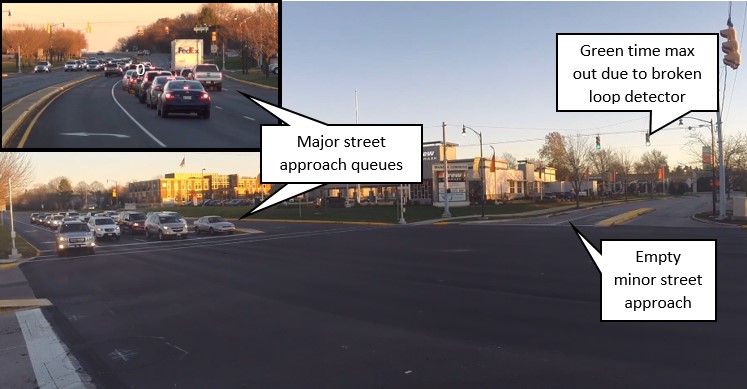

While the above case highlights traffic signal systems in particular, a similar story can be told for other types of TSMO assets, such as freeway ITS equipment, signage, etc. Much of the current need stems from a lack of documentation of quantifiable benefits associated with the timely maintenance and repair of these assets. The pavement management community, for example, has developed a robust body of literature to estimate the improvements to pavement roughness that are afforded by activities ranging from routine crack sealing to full-depth reconstruction. These benefits can then be translated into long-term monetary cost savings for an agency. In contrast, for a relatively common TSMO maintenance issue, repairing broken traffic signal loop detectors, there has been very little research that shows the adverse impacts caused by a minor street signal phase that unnecessarily forces off during peak hour travel, due to the signal controller not having the necessary detection data to efficiently allocate green time. This not only includes reduced travel time reliability, but increased agency staff time that must be devoted to handling the inevitable phone calls from drivers on the corridor.

As a TSMO community, it is imperative that we move the conversation on infrastructure management forward in 2016, especially in light of new performance measures being developed under the auspices of MAP-21 and the recent FAST Act legislation. The ability to quantify the benefits associated with keeping TSMO assets in a state of good repair will be critical to securing increased funding from federal, state, and local policymakers. Furthermore, being able to directly communicate how this funding can improve the day-to-day travel experiences of the general public will pay significant dividends in the realm of government transparency and fiduciary responsibility.