A New Institutional Approach to Operations, By Charlie Wallace, Ph.D.

Advances in technologies have transformed public agencies involved in the provision of transportation and public safety from largely stove-pipe, highway-focused entities into multi-faceted, multijurisdictional, and multimodal organizations. Highway Departments have become Departments of Transportation (DOTs) with operational jurisdiction over not only highways, but all modes of transportation.

As DOTs become more concerned with the operation of highway facilities, the impacts of both recurring and non-recurring congestion have gained an increasing priority within DOTs. Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) offer tools not earlier available to help mitigate congestion and respond to traffic incidents and emergencies. Traffic Incident Management (TIM) is becoming—and in many jurisdictions has already become—a multi-disciplinary, multiagency effort to rapidly clear highway incidents and restore normal operations.

To help DOTs in the efficient deployment of ITS, they have developed explicit ITS and/or TIM Programs, often within the Office of Traffic Operations and Engineering (OTOE), or similar names. ITS Programs are usually guided by ITS Strategic Plans, ITS Deployment Plans, or the like. TIM Programs tend to focus on processes for clearing incidents, but their Strategic Plans, if any, are generally without a vision of optimizing operations per se, or in other words, if they do have a TIM Strategic Plan, it is usually process-centric, rather than representing truly strategic thinking. These programs, and plans, often tend to be focused on implementation of ITS and/or TIM and do not well address the outcomes of the deployments that are desired. Many do not even have explicit goals and objectives that they are trying to achieve, particularly regarding pubic safety. After all, the safest condition for traffic is to be moving at a steady flow rate and speed with minimal perturbations in the flow.

Recognizing that traffic crashes and other incidents cause an unacceptable loss of life, serious injuries, and tremendous property damage throughout our nation, DOTs, under the leadership of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) have developed Strategic Highway Safety Plans (SHSPs, which in this article also stands for Strategic Highway Safety Programs) to help states focus on issues that lead to a disproportionate number of these incidents, and to propose measures to mitigate those causal activities. Generally, these tend to be actions that reflect poor behavior on the part of drivers, such as inattention, distractions, speeding, careless driving, and the like, and on driver groups that contribute disproportionately to these incidents, such as teenage and impaired drivers. As a result, few SHSPs include measures that deal directly with traffic operations per se, except for intersection crashes, which is a common focus area. Even in these cases, the opportunities afforded by ITS to mitigate such crashes are too seldom addressed in the SHSPs. Perhaps more surprisingly, TIM is hardly ever mentioned at all in SHSPs. The developers of these plans, and thus the responsible office, is always the DOT’s Safety Office, which too rarely has any direct liaison with Traffic Operations.

Severe incidents such as hurricanes, wild fires, earthquakes, and other catastrophic events have long led governments at all levels to form emergency management resources to plan for and manage responses to such emergencies. These organizations were often founded within the law enforcement community. After the horrendous experience of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001—commonly referred to as 9/11—followed by the unprecedented catastrophe wrought by Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Government issued a number of Homeland Security Presidential Directives that, along with the authorizing legislation, led to the creation of a major new branch of government—the Department of Homeland Security and its counterparts at the state and local levels. A new set of policies and procedures were issued that reshaped Emergency Management (EM) in this country, most notably the creation of Emergency Management Agencies (EMAs) across all states and in many regional areas.

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Framework (NRF) formed the core of a series of guidance documents that have transformed EM throughout the nation. Unfortunately, these new EMAs tend to be highly parochial and have not been as inclusive of other disciplines as they might, particularly the transportation community. After all, any response to any emergency will have to use the transportation network in some form, yet the Statewide Emergency Management Plans (SEMPs, or Emergency Operations/Management Plans, EOP/EMPs) developed by states and local agencies typically do not fully engage the resources of the transportation community, particularly transportation technologies and TIM. Even though their Emergency Support Function Number 1 (ESF#1) is in fact usually Transportation, the focus of most ESF#1 plans is on evacuation resources, with little to no attention to (traffic) operational issues.

It should be obvious from the above that another issue concerning all of the programs mentioned, including their guiding policies and principles, is the lack of cross-talk among them. Are the various agencies and even several departments within agencies coordinating with each other to ensure the most comprehensive—and integrated—policies and procedural plans and practices possible?

While capacity restraints are a major cause of “routine” recurring congestion, unexpected incidents, referred to as non-recurring congestion (e.g., vehicular crashes, debris on the roadway, vehicle stalls, etc.), cause considerably more congestion and the accompanying delay, wasted time and fuel, and frustration to all highway users.

DOTs, and their local counterparts, have become increasingly concerned about, and involved in, the handling of incidents, which earlier were almost exclusively the providence of police, except for roadway clearance and repairs to damaged highway infrastructure. More recently, however, DOTs have formed interdisciplinary TIM Teams that include operations and maintenance personnel from the DOT, police, wrecker operators, and others involved in incident management, which is a move in the right direction. DOTs also operate Safety Service Patrols (SSPs) to help manage incidents. And, of course, they operate Traffic or Transportation Management Centers (TMCs) that operate a large array of ITS devices used to manage both recurring and non-recurring congestion.

BACKGROUND

To attempt to answer the questions raised above, or even just to shed light on the extent of interagency collaboration, the Transportation Safety Advancement Group (TSAG), which is a committee of the Intelligent Transportation Society of America (ITSA), undertook a study to survey of states to address this and related questions expressly in the development of strategic plans in these various areas. The study was called “Analysis of State and Local Transportation Plans,” and was funded in part by the Research and Special Projects Administration (RITA) of the U.S. Department of Transportation. [1]

The survey was designed to capture information about the current status of state-level ITS and TIM Strategic Plans and SHSPs to determine to the extent that they include technology-based strategies for Public Safety, including Traffic (highway) Incident Management, and Emergency Management, and to determine to what extent there was cooperation and coordination among the parties that make up these various programs. Namely, the survey was primarily interested in the application of ITS and related technologies, and processes that use these tools, in incident and emergency response to enhance safety, capacity, and effectiveness of the response, and how this is translated into policies, plans, protocols, and practices.

This article resulted directly—and in a more significant sense, indirectly—from the author’s knowledge gained in this study.[2] The purpose of this article is to encourage more integrated, interagency/multijurisdictional planning and preparation for, response to, and recovery from both recurring and non-recurring situations that threaten safety of the traveling public and our economy.

AN EPIPHANY—THIS IS ALL ABOUT OPERATIONS

The original scope of the aforementioned study was focused on the four programs mentioned above; although in the case of EM, we looked at both the statewide EM programs, specifically their SEMPs, as well as DOT-specific Emergency Transportation Operations (ETO), as reflected in their ETO Plans (ETOPs).

The study scope only addressed traffic operations in the broader sense indirectly. In recent times, increasing focus has been placed on Management and Operations (M&O) of the highway system.[3] Indeed, the more popular moniker today is “Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSM&O),” or similar. Several respondents to the study indicated they were active in operations in general and TSM&O in particular, although this was not explicitly included in the survey.

TSM&O embraces a wider range of interests, activities, and institutions than ITS, TIM, or other somewhat “stovepipe” avocations; indeed, they are the tools of TSM&O.[4] The interests of DOTs in TSM&O are rapidly expanding beyond freeways and major arterial routes, and typical highway traffic, to also be concerned with transit, commercial vehicles, and even bike and peds of (near) equal interest. For example, Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) epitomizes the broadening of DOTs’ interests in more than just the freeways and often includes public transportation elements.

TSM&O embraces a wider range of interests, activities, and institutions than ITS, TIM, or other somewhat “stovepipe” avocations; indeed, they are the tools of TSM&O.[4] The interests of DOTs in TSM&O are rapidly expanding beyond freeways and major arterial routes, and typical highway traffic, to also be concerned with transit, commercial vehicles, and even bike and peds of (near) equal interest. For example, Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) epitomizes the broadening of DOTs’ interests in more than just the freeways and often includes public transportation elements.

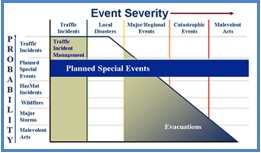

TSM&O covers more than routine recurring congestion issues; indeed, of more impact are the non-recurring incidents that we call traffic and emergency incidents. The recently released “Guide to Emergency Response Planning at State Transportation Agencies” stressed the needs for recognizing a continuum of responses to different levels of incidents and their severity.[5] The updated FHWA Web site for Emergency Transportation Operations for Disasters posted an excellent graphic depicting this continuum.[6],[7] The point is that as the severity of incidents increase, the responders and other players range from purely local (e.g., police, fire, local DOTs, etc.) on the left side, to regional, statewide, and even federal agencies toward the right.

TSM&O covers more than routine recurring congestion issues; indeed, of more impact are the non-recurring incidents that we call traffic and emergency incidents. The recently released “Guide to Emergency Response Planning at State Transportation Agencies” stressed the needs for recognizing a continuum of responses to different levels of incidents and their severity.[5] The updated FHWA Web site for Emergency Transportation Operations for Disasters posted an excellent graphic depicting this continuum.[6],[7] The point is that as the severity of incidents increase, the responders and other players range from purely local (e.g., police, fire, local DOTs, etc.) on the left side, to regional, statewide, and even federal agencies toward the right.

FHWA defines TSM&O as "an integrated program to optimize the performance of existing multimodal infrastructure through implementation of systems, services, and projects to preserve capacity and improve the security, safety, and reliability of our transportation system." Their Regional Concept for Transportation Operations suggests some examples of TSM&O strategies as follows:[8]

- Traffic incident [including emergency] management.

- Traveler information services.

- Traffic signal and arterial management.

- Transit priority systems.

- Freight management.

- Road weather management.

While these might seem familiar in the ITS world, TSM&O looks beyond the highway system traditionally associated with ITS and operated by state DOTs, and embraces multiple jurisdictions, agencies, and modes; all levels of the highway infrastructure; and other non-transportation disciplines. Indeed, one way to view this is that ITS is the technology component of TSM&O, dealing primarily with the hardware and software systems, which TSM&O integrates that with all of the institutional and human elements of transportation management.

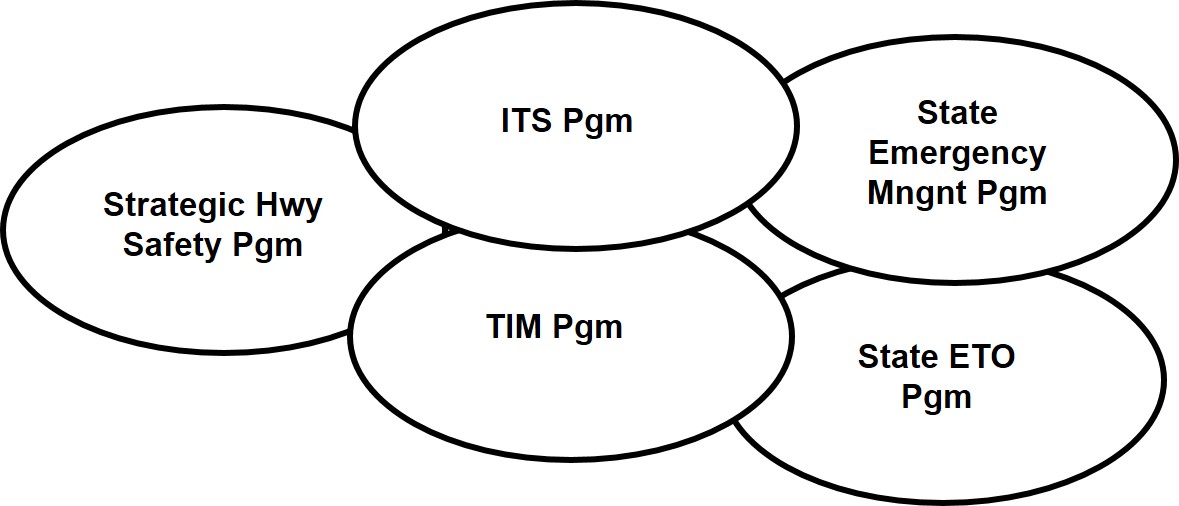

From a program perspective, Figure 1.A illustrates that there is—or at least should be—overlap between ITS and TIM, ETO, statewide EM, and SHSPs. In reality, there may not be even as much overlap, that is common purpose and activities, among these as implied in the figure.

- Traditional Program Interrelationships

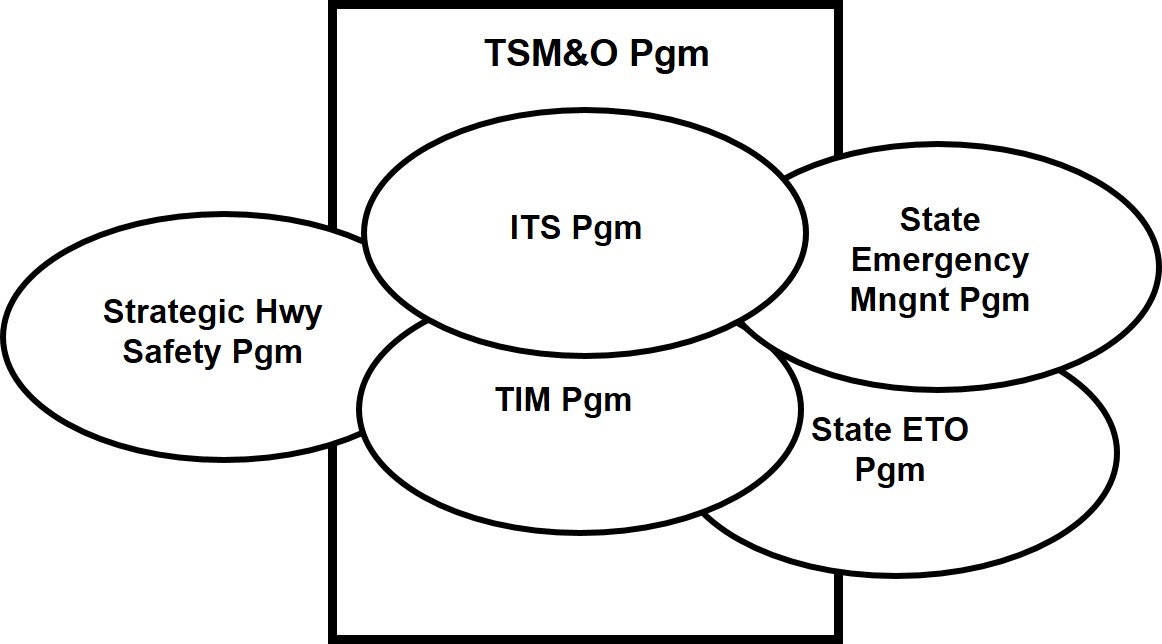

- Program Interrelationships with TSM&O

Figure 1. Relationship of TSM&O with Operations, Safety, and Incident Management Programs

If the integration of these various programs is more complete, as recommended in this article, and then coupled with the overarching coverage of TSM&O, the B part of this figure illustrates how systems and services can—and should—work better together to fulfill the vision articulated in the definition of TSM&O given above.

As the lower graphic illustrates, there are still parochial activities of several program areas that will continue to be outside TSM&O. In the EM areas, there are many activities that do not directly impact, or are impacted by, the transportation system. Currently the largest coverage of safety issues by SHSPs lies in the human behavioral realm, rather than traffic operations. ITS and TIM, however, are virtually entirely within the umbrage of TSM&O.

One might ask, “what about the other aspects of traffic operations?” Certainly there are other programs inherent within the TSM&O framework, namely outside the ellipses but within the box, namely:

- Traditional Traffic Operations (e.g., signs, markings, signals, etc.),

- Traffic Engineering (e.g., studies, standards, etc.),

- Construction Operations (likely via liaison with the Construction Office),

- Maintenance Operations (ditto with Maintenance),

- Toll Operations/Electronic Toll Collection (ditto with Toll Ops).

- Commercial Vehicle Operations (ditto with the CVO element)

- Public Transit Operations (ditto with the PT Office), and even

- Peds and bikes.

As further hard evidence of this trend toward TSM&O as an overarching vision of transportation management, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Subcommittee on Systems Operations and Management (SSOM) recently changed its name to Transportation Systems Management and Operations (TSMO). The Transportation Research Board (TRB) has the Committee on Regional Transportation Systems Management and Operations (RTSMO or Committee AHB10). The Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) has its Management and Operations/ITS Council. In addition to TSAG, ITS America’s Transportation Management Forum has a number of committees closely related to TSM&O.

Perhaps most significantly, AASHTO created the National Operations Center of Excellence (NOCoE), which is physically housed adjacent to AASHTO’s Washington, D.C., offices.[9] This center, which officially launched in January 2015, is designed to provide transportation agencies with a centralized and comprehensive set of resources for TSM&O specialists (see http://www.transportationops.org/). NOCoE is a collaborative effort of AASHTO, ITE, and ITSA, with support from FHWA.

Perhaps most significantly, AASHTO created the National Operations Center of Excellence (NOCoE), which is physically housed adjacent to AASHTO’s Washington, D.C., offices.[9] This center, which officially launched in January 2015, is designed to provide transportation agencies with a centralized and comprehensive set of resources for TSM&O specialists (see http://www.transportationops.org/). NOCoE is a collaborative effort of AASHTO, ITE, and ITSA, with support from FHWA.

Among the services NOCoE provides (or will) are best practice peer exchange, Webinars, national and regional conferences and workshops, the dynamic Web portal linked above, and on-call assistance to states and other agencies to identify best practice material and other resources for specific policy and technical issues.[10]

FHWA has also published a handbook, "Creating an Effective Program to Advance Transportation System Management and Operations: Primer,” for introducing a TSM&O Program. It includes several examples of states that have already initiated programs, namely Florida and Virginia.[11]

Several other states also have TSM&O programs, notably New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and likely others. One of the strongest expressions of the importance of TSM&O (although not referred to by that name) revealed in the aforementioned study came from the Pennsylvania DOT. PennDOT’s “Transportation Systems Operations Plan” (2005)[12] states, “PennDOT has determined that it must embrace and evolve an operational paradigm [emphasis added], even though the hour is still early. ‘Operations’ is an important wave of the future, PennDOT has concluded. Moreover, an operations program is essential to PennDOT more aptly serving the transportation needs of its citizens. The Transportation Systems Operations Plan (TSOP) ... is the outgrowth of PennDOT’s initial operations planning efforts.”

The TSOP has four stated goals:

- Build and maintain a transportation operations foundation,

- Improve highway operational performance,

- Improve safety, and

- Improve security.

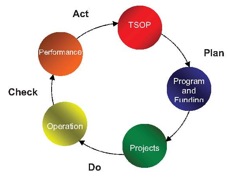

These are noteworthy in that all four directly or indirectly refer to traffic operations or safety; indeed, the TSOP document goes on to say, “Incident management and traveler information has [sic] applicability to all four goals.” The TSOP fully embraces ITS and TSM&O (see Figure 2, which is from the TSOP report).

So, what other programs already support this TSM&O concept? FHWA, along with several states already have such on-going programs as these: Regional Planning for Operations, Regional Interagency Partnerships, and the Institutional Capability Maturity Model, to name a few.

No doubt there would be challenges to implementing an over-arching TSM&O Program as conceptualized here: institutional, programmatic, administrative, and logistical to name a few. If there is interest in a dialog on this concept, we can explore examples of the supporting programs noted in the previous paragraph, as well as a concept for what might be called a TSM&O Strategic Plan. In conclusion for now, I offer the recommendations in the following section.

Figure 2. PennDOT’s TSOP Cycle[13]

OVERARCHING RECOMMENDATIONS

As stated previously, “The purpose of this article is to encourage more integrated, interagency/multijurisdictional planning and preparation for, response to, and recovery from both recurring and non-recurring situations that threaten safety of the traveling public and our economy.” These situations range from everyday congestion, through traffic incidents, to bona fide emergencies.

The following summarize some policy and programmatic actions that can lead to an effective over-arching TSM&O Program.

Institutional

These are recommendations of an organizational nature:

- Form a Regional (Transportation) Operations Organization (RTO/ROO) or coalition that encourages partner agencies to think more thoroughly in terms of inter-disciplinary, interagency planning, programming, deployment, and management and operations.

- Embrace the 4-Cs of TIM (communication, cooperation, coordination, and consensus) and 4-Es of safety (education, enforcement, engineering, and emergency services) as the foundations of the partnership, but applied program-wide.

Paradigmatic

These are recommended to develop an operationally-oriented philosophy:

- Develop an operations-based approach to managing the transportation system and its related functions to achieve safe and efficient outcomes, as opposed to purely deployment-related goals, as implied by PennDOT.

- Roll this operations paradigm into a truly broad-based Transportation Systems Management and Operations Program, with traffic surveillance and control, incident and emergency management, and public safety and security as the pillars of the program.

Programmatic

- Recognize the values of the interagency, multijurisdictional approach, but respect the parochial interests and needs of the several program areas as well.

- Consider co-location of some of these, or at least effective linkages among all to share data, information, images, and decision making: Transportation Management Centers, Traffic Control Centers, Emergency Operations Centers, Public Safety and/or Emergency Service Dispatch Centers, 9-1-1 Centers, and Intelligence Fusion Centers.

- Develop Concepts of Operations covering traffic management, incident and emergency management, and public safety and security, but with linkages between them for shared roles and responsibilities.

- Define outcome-based performance measures by which the success of the policies, practices, and efforts can be evaluated in each area.

In closing, recall an early mantra from the ITS world that applies equally to the operations paradigm encouraged in this article and all of the program areas discussed: “Think globally, plan regionally, and deploy locally.”

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

4-Cs Communication, cooperation, coordination, and consensus (of TIM) [In some places, “commitment” replaces “consensus.” Also sometimes referred to as only three, omitting the last “C”, and some have even suggested five, adding “compromise” or “creativity.”]

4-Es Education, enforcement, engineering, and emergency services (of highway safety)

9-1-1 The national emergency call-in number

AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials

DOT Department of Transportation

EM Emergency Management

EMA Emergency Management Agency

EOP Emergency Operations Plan

ESF(#1) Emergency Support Function (Number 1, usually Transportation)

ETO(P) Emergency Transportation Operations (Plan)

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

ICM Integrated Corridor Management

ITE Institute of Transportation Engineers

ITS Intelligent Transportation System

ITSA ITS America

M&O Management and operations

NCHRP National Cooperative Highway Research Program

NIMS National Incident Management System

NOCoE National Operations Center of Excellence

NRF National Response Framework

OTOE Office of Traffic Operations and Engineering (of a DOT), or just TO

PennDOT Pennsylvania Department of Transportation

PPP or P3 Public-Private Partnership

PTO Public Transit Operations/Office

RITA Research and Special Projects Administration

ROO Regional Operations Organization

RTO Regional Transportation Organizations

RTSMO Regional Transportation Systems Management and Operations (Committee AHB10 of TRB)

SEMP Statewide Emergency Management Plan

SSOM Subcommittee on Systems Operations and Management (AASHTO)

SSP Safety Service Patrol

TSMO (Subcommittee on) Transportation Systems Management and Operations (AASHTO)

TIM Traffic Incident Management

TMCs Traffic/Transportation Management Centers

TO Traffic Operations (Office)

TRB Transportation Research Board

TSAG Transportation Safety Advancement Group (of ITS America)

TSMO (Subcommittee on) Transportation Systems Management and Operations (AASHTO)

TSM&O Transportation Systems Management and Operations

TSOP Transportation Systems Operations Plan (Pennsylvania)

[1] While much of the material in this article, including explicit use of some of the text, was taken directly from a draft report submitted for the project—which has not been published by ITSA or anyone else—the specific concept proposed in this article was not part of the project scope.

[2] Note that the actual results of the project survey were for internal use by TSAG and were not published.

[3] In the past, transportation agencies have referred to Operations and Maintenance (O&M) of specified components of the system, such as the roadways themselves, and some still do. In the operations sector, however, M&O has become more vogue, and maintenance per se is considered an important part of operations. The new emphasis, however, is on managing the traffic using multiple components of the transportation system, and—more importantly—the skills of those who operate the system.

[4] TSM&O logo courtesy of the Florida DOT; used with permission.

[5] Wallace, C.E., A. Boyd, Jason Sergent, A. Singleton and S. Lockwood, "A Guide to Emergency Response Planning at State Transportation Agencies," prepared for NCHRP Project 20-59(23), published by the Transportation Research Board as NCHRP Report 525 Surface Transportation Security, Volume 16, 2010.

[7] On the above Web site, the caption to the graphic states, “This chart shows Emergency Transportation Operations as a continuum that is defined by the Probability an Event will occur and the Severity of the Impact & Complexity of Response. The areas not shaded are generally handled by state and local authorities and—for the most part—do not need standardized policies, processes and protocols outside of those prescribed by the National Incident Management System.” Some might take issue with the last sentence. NIMS sets a framework for all incidents, and any level, but it does not offer the policies, processes, and protocols that agencies need to address specific incidents, otherwise we would not need TIM Plans, EOPs, and the like. A more accurate view, perhaps, is that the application of NIMS principles would be less stringent in the first two columns, traffic incidents also being mostly handled by state and local authorities.

[9] NOCoE logo used with permission.

[10] And, of course, the author appreciates the support of the NOCoE in posting this article on the site.

[11] "Creating an Effective Program to Advance Transportation System Management and Operations: Primer," Report No. FHWA-HOP-12-003, January 2012. Available at http://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop12003/fhwahop12003.pdf.

[13] Source: “Transportation Systems Operations Plan,” Pennsylvania DOT, 2005.