Measuring Safety Performance – For the Federal Government and Your Own Agency

By Heather Rothenburg, PhD, Director of Policy and Federal Projects, Sam Schwartz Engineering

Historically, measuring the number of fatalities from one year to the next has been the most commonly used safety performance measure. The availability of a standardized national dataset (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS)) allows federal, state, regional, and local transportation agencies to track a common safety measure from a single data source. More recently, transportation agencies have expanded the idea of measuring safety performance to include a measure of exposure (usually vehicle miles traveled), serious injuries, and even more specific measures at the state or local level. Safety impacts mobility not only in terms of the people immediately involved in the crash, but congestion and secondary crashes related to that primary incident. It may even impact how road users make decisions about where, when, and how they travel.

In March 2014, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) began the process to formalize a series of performance measures in relation to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). These measures represent an increased federal focus on performance management, but transportation agencies should not rely solely on these measures to understand the effectiveness of their safety programs. This article will provide a brief summary of the safety performance measures proposed by the USDOT, along with a series of other considerations for establishing performance measures that are meaningful to effective safety program implementation beyond federally required reporting.

Brief Summary of USDOT National Performance Management Measures for the Highway Safety Improvement Program

USDOT published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in March 2014 addressing the requirements in the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) to focus on performance management as a means for transforming the Federal-aid highway program through increased accountability, transparency, and improved decision-making. The NPRM proposes the following for safety performance measurement associated with FHWA’s HSIP:

-

Process to be used by State DOTs and Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) to establish safety-related performance targets;

-

A methodology to be used to assess State DOTs compliance with the target achievement provision specified in 23 USC 148(i);

-

Process State DOTs must follow to report on progress toward the achievement of safety-related performance goals; and

-

Key definitions.

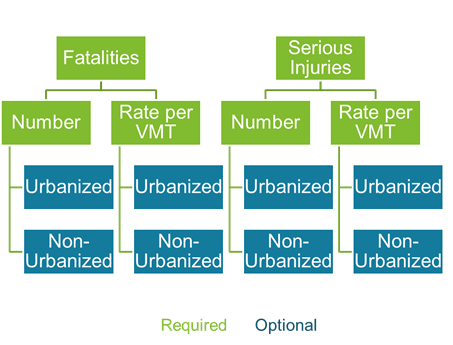

States will be required to set and report on progress toward targets for the number of fatalities and serious injuries as well as the rate of each per VMT. In addition, they will have the option of reporting on these stratified by urbanized and non-urbanized roads, as illustrated in Figure 1.

States are required to achieve their target or make significant progress toward reaching it. State DOTs that have achieved their overall safety targets would not need to demonstrate significant progress. FHWA would consider a State to have made significant progress toward achieving each target if the actual outcome for each target is at or below the upper bound of a 70 percent prediction interval, which would be set based on the projection point from a 10-year historical trend line.

Figure 1. National Performance Management Measures, HSIP NPRM.

FHWA would consider a State DOT to have made overall significant progress if they have achieved or made significant progress on at least 50 percent of the targets they set. For a State that has chosen to set only the required 4 targets, they must achieve or make significant progress on at least 2. If a State opts to set urbanized and non-urbanized targets, they must achieve or make significant progress on at least 50 percent of the ones they choose to set.

If a State fails to achieve or make significant progress toward at least 50 percent of the targets it chose to set, it will be required to do the following:

-

Obligate a portion of their HSIP funding only for highway safety improvement projects, and

-

Develop and submit an annual implementation plan to document how they intend to improve performance using HSIP funds.

Building on Federally Required Safety Performance Measures for Meaningful Program Implementation

Transportation agencies seeking to institutionalize data-driven decision making through performance measurement should consider using the federally required measures as the foundational elements of an expanded set of safety performance measures. These expanded safety performance measures should account for the following:

-

What are the agency’s programmatic and policy goals? Many agencies may already be measuring a decrease in crash frequency or severity for specific problem areas (e.g., pedestrians or roadway departure crashes) through efforts such as the state’s Strategic Highway Safety Plan. Agencies may also seek to measure administrative actions as part of their safety programs. For example, if an agency has workforce recruitment or retention goals, the safety program may elect to measure recruitment and retention of agency staff associated with safety programs. This can be especially important as resources are limited and safety becomes a secondary responsibility of staff focused on other program areas.

-

Should the safety program measure output as well as outcome? Measuring fatalities and serious injuries – or even crashes in general – focuses on the outcomes. Outcome measures may be influenced by external factors such as the economy, weather, etc. Output measures provide a more direct understanding of a safety program’s efforts. Output measures for safety should focus on the implementation of countermeasures known to be effective. One example of an outcome measure would be implementation of one or more of FHWA’s Proven Safety Countermeasures.

-

Can the safety program establish aspirational targets? Agencies may shy away from setting aspirational goals for fear of being criticized for not achieving them. Perhaps the most common highway safety aspirational goal is zero fatalities, as demonstrated by Toward Zero Deaths and Vision Zero campaigns. Setting achievable goals is important to demonstrate measured progress. Setting aspirational goals is important to send and important message and to encourage broader, sweeping commitments to safety programs.

-

Can measures consider preventive efforts rather than reactionary ones? Measuring crash frequency and severity is a lagging indicator. The negative outcome has already occurred. Can the agency identify preventive measures, such as the use of practices like FHWA’s Systemic Approach, to identify potential risk areas and address them before the crash occurs?

Importance of Data in Performance Measures

One of the greatest challenges associated with performance measurement is the availability of reliable, timely data. Often, agency staff charged with identifying performance measures and tracking progress are held hostage by their data. Being held hostage by data includes the following challenges:

-

We rely on “best available” data rather than striving for the best data. Leveraging existing data sources can be invaluable, especially in a resource-constrained environment. However, agencies should identify what data is necessary to establish meaningful performance measures, develop a strategy for collecting that data, and allocate resources to implement that strategy. Using existing data is a short term solution while planning for ideal data is a long term approach.

-

We confuse causation with correlation. It is easy to note common trends during a given period of time and make inappropriate assumptions that there is a relationship between them.

-

We make do with old data. Fatality data from FARS is typically available in a preliminary format 9 months after the end of the calendar year and in final format one year after that. This means decisions are being made based on data that is at least 2 years old. Many states have more timely electronic crash data systems. Other data including program implementation information may be available almost immediately. This data can be used to more effectively make decisions and measure progress at points in time where meaningful decisions can be made about the direction of the safety program’s efforts.

-

We make decisions on data presented out of context. Data dashboards are increasing in popularity, and can be a valuable tool to present a variety of information in a concise manner. It’s important to remember, though, that they often lack historical or future information that is critical to a true understanding of what is being presented.

-

We aim for standardization and uniformity rather than customization. USDOT is charged with collecting standardized information from a variety of agencies. This leads them to rely on data and establish measures that are as uniform as possible (such as fatality data). However, other agencies don’t face the same constraint and should establish measures that are meaningful, rather than using only the federally required measures.

Conclusion

Federally-required performance measures should represent only the beginning of safety performance measures in transportation agencies at all levels. Building on this foundation, State and local agencies should develop a cadre of measures that are 1) meaningful, 2) timely, and 3) address short term issues while focusing on long term safety program development.